Timely justice: How case screening improves efficiency, effectiveness, and fairness

Evidence from a randomized controlled trial

By Justice Innovation Lab Staff

Go to:

Experimental design and data

Experimental design

Prosecutor offices across the U.S. are generally structured in one of two ways: "horizontal" or "vertical." In horizontal prosecution offices, prosecutors are put into groups that perform specialized parts of the prosecution process. For instance, an office might have a case screening section, a charge filing section, and a trial section, where a single case is passed from section to section with different attorneys handling different parts of the prosecution. Conversely, in a vertical office, like the Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office (SOL9), cases are assigned to a single attorney at the outset who performs all functions necessary in prosecuting (or not) the case. Many offices employ a mixed approach based on specialized prosecution units and certain crimes. Despite this difference in approach, as stated in the Oxford Handbook of Prosecutors and Prosecution, "there is no research comparing the effectiveness of vertical and horizontal prosecution." This study looks to fill that gap.

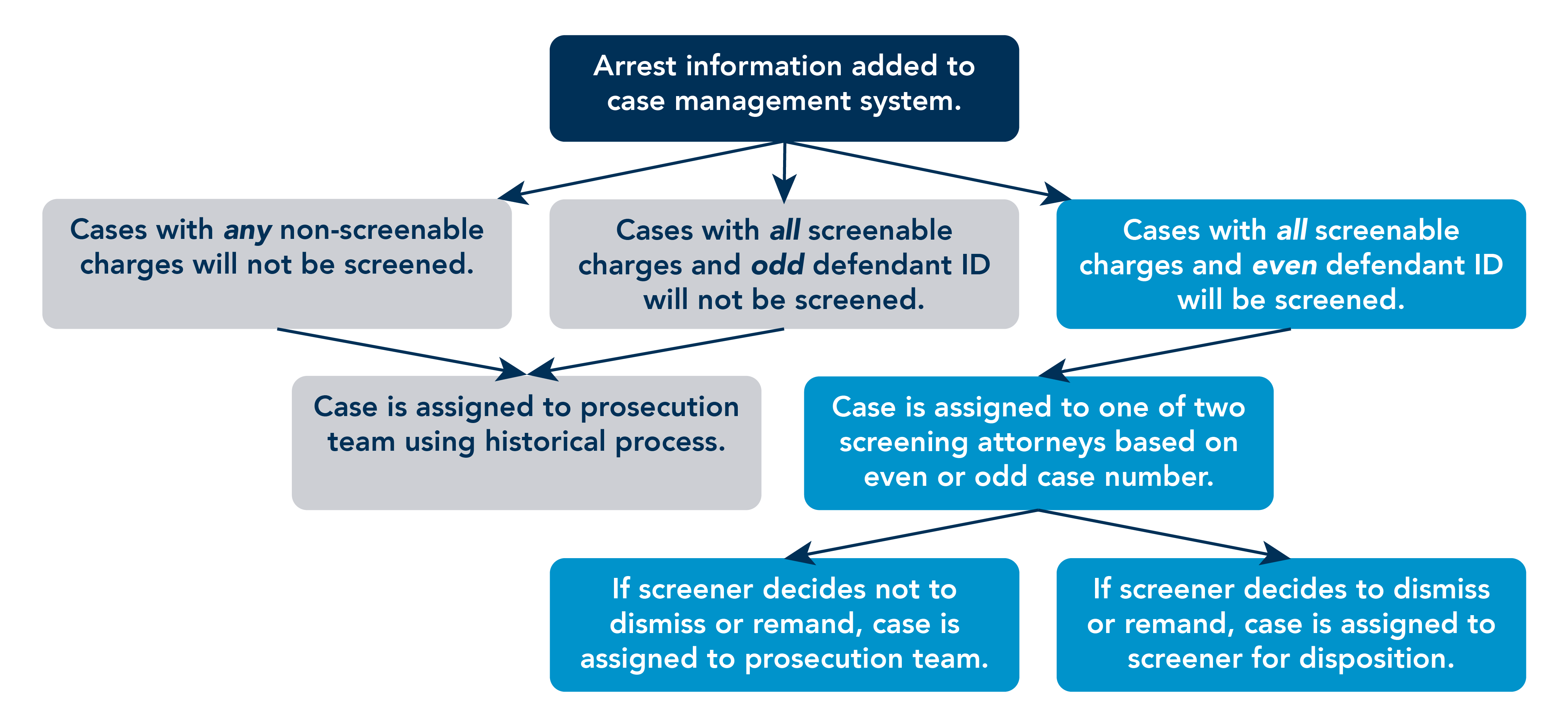

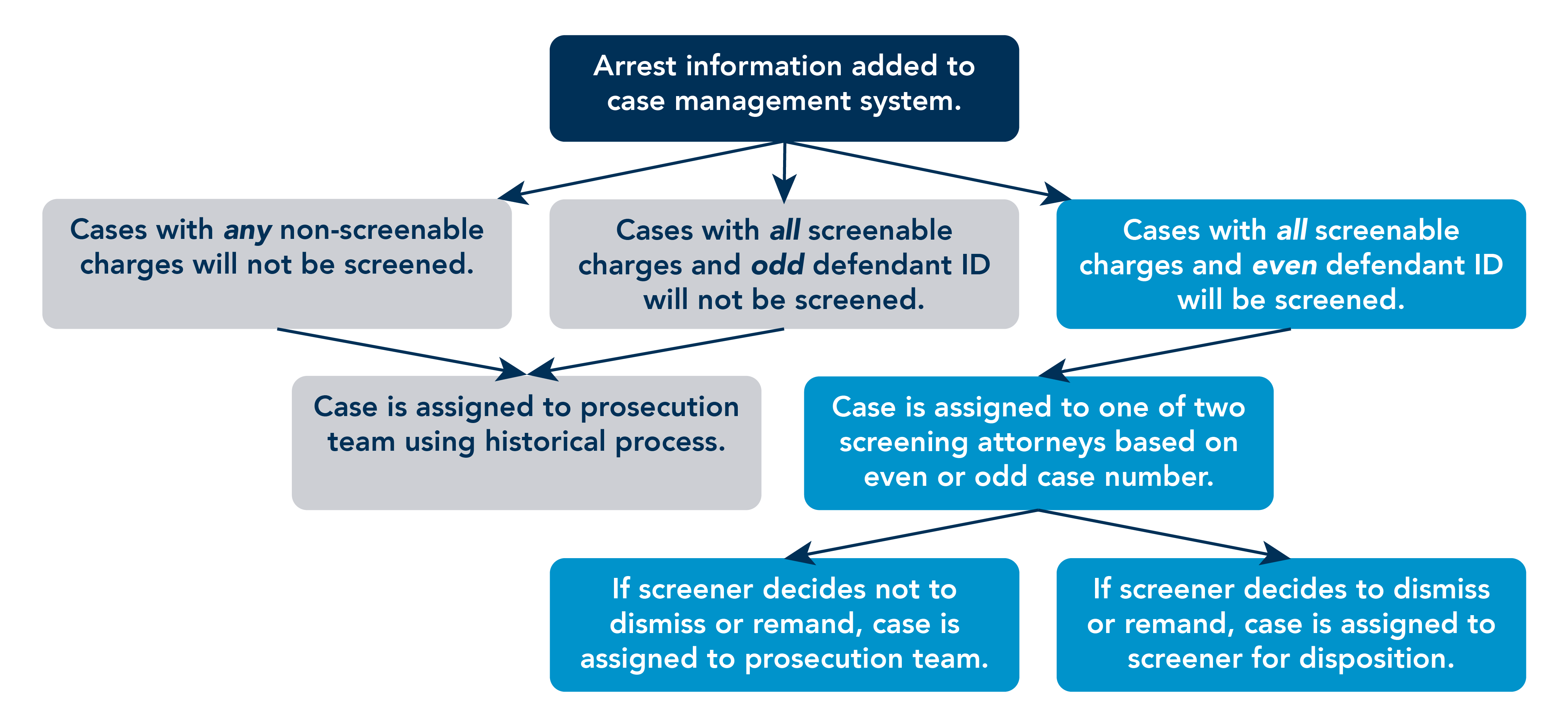

To rigorously evaluate the screening process, SOL9 partnered with Justice Innovation Lab (JIL) to design a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Under the new framework, when a case with only low-level charges was referred to the office, it was randomly assigned to either the screening unit (the "treatment" group), or a line prosecutor in accordance with standard practice (the "control" group). The diagram below shows the RCT case flow process. For the screened cases, one screening attorney handled 40% of cases, while the second handled the remaining 60%. The screeners reviewed eligible cases using preliminary information such as incident reports and criminal histories to quickly identify cases that should be:

For the screened cases, one screening attorney handled 40% of cases, while the second handled the remaining 60%. The screeners reviewed eligible cases using preliminary information such as incident reports and criminal histories to quickly identify cases that should be:

- Dismissed for insufficient evidence

- Remanded to lower courts

- Passed on to line prosecutors for further prosecution decisions

For each case, screeners documented their decision-making process in the case management system and completed a survey about case and defendant characteristics. If the screening attorney did not dismiss or remand the case, it was passed on to a line prosecutor for further review and possible prosecution.

The experimental design included measures to account for complications such as co-arrestees (all co-arrestees in a case were treated the same way) and arrestees with multiple cases (a defendant's ID remained the same across cases, ensuring consistent treatment).

Note that the report findings presented here are based upon an analysis comparing cases that were screened to cases that were not screened. The analysis does not follow a rigorous intention-to-treat (ITT) methodology. Justice Innovation Lab is conducting an ITT analysis that aligns with an OSF pre-registration plan and will be presented at a later date.

Data

Our data come from the case management system for the Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office of South Carolina, which prosecutes all felonies and serious misdemeanors in the circuit. The office provided us with records of all cases presented between January 2017 and April 2025. These records include information from police departments and courts, as well as prosecutor decisions about charging and dismissals. We receive weekly data extracts and work with the office's Case Management Team to ensure data quality.

To help screening attorneys easily identify which cases to review, the Case Management Team created a daily automated report in their system. The two screening attorneys review this list and assess cases as soon as the necessary documentation becomes available—primarily police reports and criminal history records. Screeners record their actions in the system, which helps us track whether cases were properly screened or were handled differently than intended (such as when a line prosecutor took a case before screening or when a screening attorney reviewed a control group case). The system captures essential information about each defendant, their charges, case outcomes, and key dates including arrest, screening, and final disposition.

The data analyzed in this report include arrests made by the four largest police departments in Charleston County, which were the departments chosen for the randomized controlled trial: Charleston Police Department, Mount Pleasant Police Department, Charleston County Sheriff’s Office, and North Charleston Police Department. Cases are divided into four distinct time frames: Pre-COVID (January 2017–February 2020), COVID (March 2020–February 2022), Pilot Screening (March 2022–April 2023), and RCT Screening (May 2023–October 2024). When comparing these periods, we limit our analysis to cases with only low-level charges that would be eligible for screening. The screening-eligible charges were deliberately selected by SOL9 to include 149 low-level drug and property crimes. For the purposes of assessing rearrest, all arrests are included, regardless of charge, as are cases arising from arrests between November 2024 and April 2025.

Over the experimental period, there were 5,602 cases in the experiment with 2,727 (48.7%) screened by one of the two screening attorneys. Across the screened and unscreened cases, there is balance across variables of interest including race, gender, age, and charges.

Noteworthy legal change

During the experimental period, the South Carolina legislature enacted the South Carolina Constitutional Carry/Second Amendment Preservation Act of 2024. This law went into effect on March 7, 2024, ten months into our experimental period. The law is an open-carry law that led to the immediate dismissal of many illegal firearm possession charges that were originally included in the screening policy. Upon enactment, SOL9 dismissed a large number of cases across both treated and untreated groups of the experiment.