Timely justice: How case screening improves efficiency, effectiveness, and fairness

Evidence from a randomized controlled trial

By Justice Innovation Lab Staff

Go to:

About

Adoption of case screening by the Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office

For years, the Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office (SOL9) in Charleston and Berkeley Counties struggled with long case processing times, even for cases that would ultimately be dismissed. Analysis of SOL9's dispositions from 2015 through 2021 revealed a troubling pattern: the median time to dismiss cases for easily identified issues, like lack of evidence, was 221 days (more than seven months).

These delays affected everyone, but not equally. Prior research by Justice Innovation Lab (JIL) found some large differences between how long it took to dismiss cases involving a Black defendant as compared to a White defendant across a variety of crime types. The Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office was determined to understand why this difference existed and to address it if possible.

Furthermore, these extended disposition times created a snowball effect on prosecutor workloads. In June 2022 there were 13,592 undisposed cases in SOL9, with 57% open longer than a year and 28% open longer than two years. Without intervention, it was estimated that clearing this backlog would take over six years. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly worsened this situation. Court closures and reduced operations created a massive backlog across the criminal justice system. Cases that might have been resolved quickly under normal circumstances languished in the system, adding to prosecutors' already overwhelming caseloads and extending the time victims and arrestees waited for resolution.

The Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office recognized that this was both an issue of fairness and a practical problem of resource allocation. Many cases were being dismissed for reasons that could have been identified much earlier in the process, such as insufficient evidence, lack of discovery from law enforcement, or elements of the crime not being met.

Over the course of a JIL-led workshop and three months of internal working sessions, SOL9 developed a solution that included dedicating a screening attorney to review cases as soon as possible after they were referred from law enforcement. This screening attorney would assess each case for legal sufficiency and possible alternatives to prosecution, quickly identifying weak cases that should be dismissed or remanded.

In May 2021, SOL9 began a pilot screening program with cases referred from the Charleston Police Department. Initial results were promising—screening resulted in increased identification of charges that should be dismissed or receive an alternative to prosecution. By implementing a formal screening process, SOL9 aimed to address multiple problems simultaneously: reducing racial disparities in case processing, decreasing prosecutor workloads, eliminating unnecessary court dates, and allowing the office to devote more resources to cases that truly warranted prosecution.

Theory of harm

When prosecutors take months to review and potentially dismiss cases, the delay itself causes significant harm to all parties in the case—arrestees, victims, the court, and the attorneys. The consequences extend far beyond simple inconvenience.

For arrestees who cannot afford bail or do not qualify for release, these delays mean spending days, weeks, or even months in pre-trial detention for charges that will ultimately be dismissed. Research shows that pre-trial detention dramatically increases the likelihood that arrestees will plead guilty, even when they are innocent. Studies by Peterson, Thomas, and Dobbie have consistently found that people held in jail before trial are much more likely to accept plea deals simply to secure their release.

These guilty pleas have lasting consequences. A criminal record makes it harder to find housing, secure employment, receive public benefits, and participate fully in society. Evidence suggests that creating criminal records for minor offenses may actually increase future criminal behavior instead of deterring it.

The harm extends beyond arrestees held in jail. Even released arrestees face multiple court appearances while awaiting resolution, each requiring time off work, childcare arrangements, and transportation to court. Many must sit for hours in courtrooms waiting for their case to be called, only to learn that the case isn't ready to proceed and they'll need to return for another hearing. Missing a court date can lead to future arrests.

For victims, extended case resolution times have a number of negative consequences. Improving case processing efficiency through screening serves victims in two main ways. First, for victims involved in screened cases, the victim is given certainty sooner as to whether the case will proceed. Under the prior process, victims might show up to court multiple times as cases are extended only to eventually have the case dismissed. Under the new process, victims are informed much sooner as to the viability of the case based upon the evidence. They may also have their cases resolved more quickly through a remand or diversion program, which often leads to defendants paying restitution to victims. Second, for victims involved in more serious cases that are not screened, the prosecutor and other support staff assigned to the case have more time to devote to their case through decreases in caseload. Furthermore, the removal of some cases from forensic testing reduces the strain on state resources that would better serve more serious cases.

Finally, for line prosecutors, defense attorneys, the court, law enforcement, and the myriad of staff that support these agencies, screening out legally insufficient or otherwise weak cases reallocates resources for these strapped agencies to cases that need serious intervention.

Identifying the root cause of the problem

To address delays in case processing, SOL9 examined how its office was structured. The Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office typically employs about 30–35 line prosecutors in Charleston County who handle thousands of cases annually, ranging from low-level drug possession to murder. The office was structured as a "vertical" prosecution office, where a single line prosecutor handles a case from start to finish. Previously, cases were assigned to line prosecutors within teams responsible for specific police departments. This approach creates continuity and develops expertise, but it can also cause bottlenecks. Prosecutors juggling many cases at different stages may postpone reviewing new cases until court dates approach, especially for seemingly less serious matters.

The problem was especially pronounced for low-level crimes. Without someone specifically tasked with early review, cases languished while prosecutors waited for all evidence to be received. In some instances, delays can result in it taking months to receive police reports or forensic evidence, such as drug tests. During this waiting period, cases remain open and hearings continue to be scheduled, which takes up valuable time for everyone involved. The structure of the office itself was therefore identified as inadvertently delaying justice, particularly for those charged with minor offenses that were ultimately dismissed.

The solution

In contrast to vertical prosecution, "horizontal" prosecution models organize attorneys by function, with different prosecutors handling specific stages of cases. This structure, more common in larger, urban jurisdictions, allows for specialization and the processing of high volumes of cases more efficiently. The Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office decided to experiment with a horizontal prosecution element in order to address extended case resolution times for low-level cases.

To do so, the office hired two experienced prosecutors part time to screen cases at the earliest possible stage based on police reports, criminal histories, and any other evidence available within 30 days of an arrest. Eligibility for case screening was based on the charges in the case, with a focus on non-violent crimes, charges with historically high dismissal rates for insufficient evidence, and cases that could be effectively reviewed using only a police report and criminal history. The most common charges were for drug possession, small-amount drug sales, and minor property crimes like shoplifting. This approach allowed the screening attorneys to concentrate their limited resources on cases where early intervention would be most impactful. The screening attorneys were given the authority to dismiss or remand a case (non-prosecution), or to pass a case on to a line prosecutor for further evaluation and possibly prosecution. This approach also cleared some of the caseload from General Sessions Court and moved it to summary courts where cases could be resolved more quickly.

Collaboration between JIL and SOL9

In 2015, South Carolina's Ninth Circuit Solicitor, Scarlett Wilson, began collecting prosecutorial data with some questions in mind: Is my office being fair? Are we using our resources effectively? Are we improving public safety? Soon thereafter, the Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office handled two of the biggest civil rights cases in the United States—the racially-motivated massacre of nine parishioners at Emanuel AME Church and the murder of Walter Scott, a 50-year-old Black man who was shot by a North Charleston Police Department officer. The city was under substantial pressure to address growing tensions, and Solicitor Wilson wanted to know whether her office could use existing data to begin resolving any problems. However, while SOL9 had collected data on key decisions regarding arrest, charging, dismissals, convictions, diversion, and sentencing, they lacked the capacity to understand the data and integrate its findings into its decision making. Justice Innovation Lab was founded to assist the Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office in analyzing its data, identifying any problematic office practices, and designing solutions to address the problems.

Our first project was to analyze racial disparities in cases prosecuted in SOL9. A review of the data found that on most decision points, prosecutors treated similarly situated defendants similarly. Nonetheless, because there are a disproportionate number of Black arrestees entering the system, there are large disparities in outcomes such as incarceration rates. For example, Black men accounted for just 12% of the population of Charleston, yet they accounted for 53% of those arrested for General Sessions offenses in 2019. Our study also found that Black men were being prosecuted for crimes that are more likely to result in a custodial sentence, such as second and third offense drug charges.

Our process

To rigorously evaluate the impact of these policy and process changes, Justice Innovation Lab followed its established approach to creating measurable, sustained change, as outlined below.

Focus on decision-makers

Our approach to developing the screening intervention centered on deep collaboration with the prosecutors who would ultimately implement and be affected by the changes. While we had identified the problem through data analysis, designing an effective solution required engaging the actual decision-makers in the process. We organized a workshop with all prosecutors in the Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office to review "The Case for Screening" report, providing them with a clear understanding of the delays in case processing and their disproportionate impact on Black arrestees. By presenting the data directly to prosecutors, we fostered ownership of both the problem and potential solutions, ensuring the intervention would address their practical concerns while achieving justice goals.

Beyond presenting information, we invested in building prosecutorial capacity. We conducted basic statistics courses for the attorneys, enhancing their ability to understand and interpret the data themselves rather than simply accepting our conclusions. This educational component was crucial—it transformed prosecutors from passive recipients of policy changes into informed participants who could evaluate evidence and contribute meaningfully to the intervention design. The prosecutors' insights about case flow, evidence collection challenges, and court scheduling helped refine which case types should be eligible for screening and how the screening attorneys should prioritize their work.

Perhaps most significantly, we facilitated dialogue between prosecutors and individuals affected by delayed case processing. These sessions created space for prosecutors to hear directly from people who had experienced months-long delays for cases that were ultimately dismissed, including those who had lost jobs, housing, or family connections while waiting. These human stories transformed abstract statistical findings into compelling narratives that resonated with prosecutors' sense of justice and fairness. By connecting the decision-makers with those affected by their decisions, we helped prosecutors recognize how structural changes to their office could significantly improve lives while also enhancing their own professional effectiveness and job satisfaction.

Understand the data

To identify areas for improvement in the Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of case disposition data from 2015 through 2021. Our team mapped the entire case flow process from arrest to final disposition, identifying key decision points and measuring the time elapsed at each stage.

We shared these findings with SOL9 through detailed data visualizations and reports that made complex statistics accessible. Rather than simply presenting the problem, we also quantified the potential benefits of a change to process. This data-informed approach helped prosecutors understand not only the scope of the problem but also the concrete benefits of implementing a solution, creating a compelling case for change rooted in both efficiency and fairness.

Drive innovation

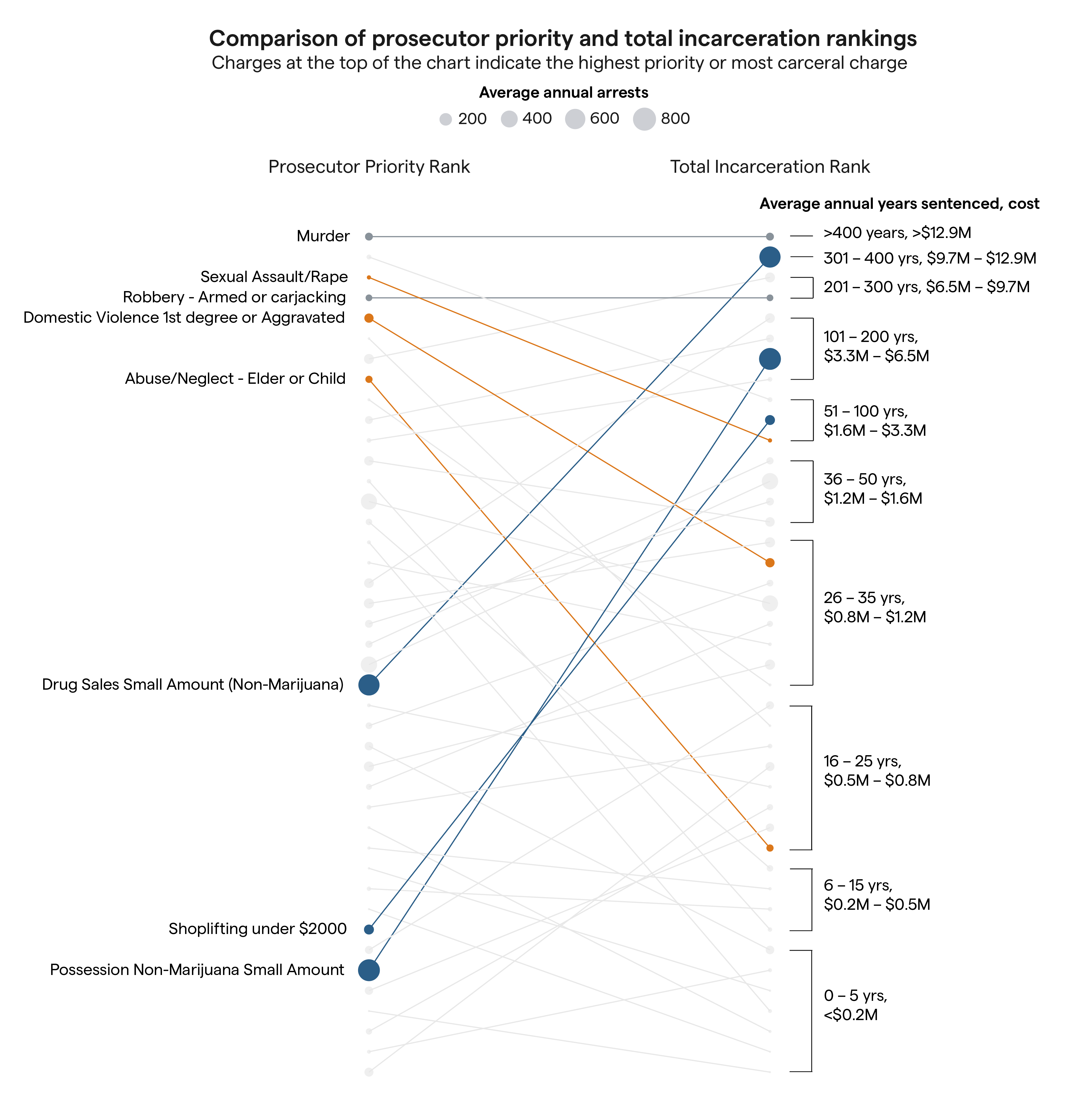

Our workshops with the Ninth Circuit Solicitor's Office transformed abstract data into actionable insights by bringing prosecutors directly into the analysis process. During the workshop, we presented findings to line prosecutors, management, and impacted community members to drive discussions regarding what the office was doing and how they defined justice. Below is an example chart used in the workshop to compare what line prosecutors work on against what they consider to be the highest priority.

The workshop concluded with the most engaging activity—teams of prosecutors "designed" possible solutions to address the issue. These solutions were then presented to a panel to determine which ideas the office would pursue. Ultimately, the office chose to create a new process to screen cases, and to set up an internal working team to further develop and implement ideas.

This internal working group then tackled questions of which charges should be included and what review criteria should be used. By working directly with the case data, prosecutors developed not just theoretical support for screening but concrete operational plans for how it could function within their office. This practitioner-centered design approach ensured that the screening intervention was developed not as an imposed policy but as a collaborative solution that addressed the concerns and priorities of the prosecutors who would ultimately implement it.

Build solutions

The office began a pilot study of the screening process to test implementation. In this pilot study, eligible charges originating from a single arresting agency, the Charleston Police Department, were reviewed by one part-time screening attorney. The pilot revealed that screened cases were more quickly identified for dismissal or remand. The study also created the evidence necessary for the office to pursue additional grant funding to support expanding the screening process. This allowed both the hiring of an additional part-time screening attorney and expansion of the screening program to include the four largest Charleston County police departments.

Implement change

After a successful pilot study, SOL9 and JIL scaled the screening program to allow for more rigorous testing through a randomized controlled trial. Changes included expanding screening to more charges and more police departments, and adding an additional screener. The office's carefully designed approach to implementing policy change created the basis for the evaluation presented here. Furthermore, this approach means that there is substantial additional research that is possible, which will be important for understanding how prosecution affects everyone involved.